Thanks to prime mover Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, San Jose now has its own "Comic-Con": the Silicon Valley Comic Con. San Jose has been home to many science-fiction/film and TV/comic-themed toy shows or conventions over the years (many of us still have fond memories of TimeCon at the old San Jose Convention Center), some of them pretty rinky-dink. In recent years, much of the excitement migrated to San Francisco for WonderCon, the Bay Area's 1987-2011 affiliate of the San Diego Comic-Con mothership. Since WonderCon's been gone, the Bay Area has a felt a void when it comes to the big-time con experience, but the excitement has moved an hour south to San Jose, where Wizard World has taken to staging shows, and now "Woz" has birthed his very own. Or, for those paying slightly closer attention, absorbed the Big WOW! Comic Fest (formerly known as Super-Con...oh, how's a casual geek to keep track?) and given it a shot in the arm.

The first-annual Silicon Valley Comic Con officially kicked off at 4:30pm Friday, March 18, 2016 with a ribbon-cutting ceremony at the San Jose Convention Center, nestled downtown between the Marriott and Hilton hotels. Soon thereafter, the show floor opened with something that looked very much like, well, WonderCon. The dealer's room inhabits Halls 1-3 with a familiar layout: Artist Alleys for comic creators, a Celebrity Row for high-priced autographs, and rows of vendors hawking comics, books, posters, toys, and the like (probiotic drink, anyone?). Innovations include a "VR Lab" for that trendy virtual-reality push, an "App Alley," and a Cosplay Corner, as well as spaces set up in the adjoining Ballrooms for the Cartoon Art Museum, Stan Lee Museum, and Rancho Obi-Wan.

The virtual reality and app ideas demonstrate Woz's big idea to marry tech to the con experience in a more concrete way, generating more interest for the innovation people love by aligning it with the entertainment people love. There's a panel devoted to the tech startup show Halt and Catch Fire and others devoted to black holes, life on Mars, and more—science to go with the fiction.

FRIDAY, March 18, 2016 ("Preview Night"):

Though there were other worthy panels and access to the con floor, the big news was the meeting of benign geek overlord Wozniak and his first big guest, William Shatner. "An Evening with William Shatner" (if an hour can be called an evening) found the 84-year-old actor in fine fettle. It wasn't hard to imagine the Shat thinking a mantra of "Get a life" as he ticked off his allotted hour with entertaining rambling, mostly seeming to enjoy hearing himself talk but occasionally whipping up the art of conversation. Things started on an awkward note when the nearly full General Session Hall/Room I greeted Shatner with an enthusiastic but not standing ovation ("Please, sit down. Oh..." Shatner joked). By the end of his time, Shatner had won enough jaded-geek love for a partial standing-o.

Let's face it: it's not every day one gets an audience with the Shat, and fans (myself included) lined up at two mics for the opportunity to ask a question. Even Woz was feeling the excitement from his front-and-center seat. Shatner spent the first quarter of his panel recounting snafus around a charity motorcycle ride, then buttering up his host (though inexplicably praising him as the man who invented the iPhone—oh, Bill!), talking of their planned dinner together, and insisting that Woz ask the first question at the mic. An obviously surprised Wozniak obliged, but didn't know what to say (he requested a poetry reading, but didn't get one, just as another fan was later denied a song). Shatner plowed on, and the two bantered amusingly about philosophy and technology before ceding the mics to fans of all ages (the kids made for the funniest moments—both they and the Shat say the darndest things).

Most of the time whiled away with talk of Shatner's new book on Leonard Nimoy (on the New York Times bestseller list, don'cha know), his horse-riding passion and his charity work, but there were some choice moments riffing about the Twilight Zone episode "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" and Shatner's once-upon-a-time showdown with the Gorn, as well.

SATURDAY, March 19, 2016:

Though Friday was bustling enough to impress, history tells us to expect big crowds on con Saturdays. Silicon Valley Comic Con did not disappoint, with tens of thousands converging on the San Jose Convention Center, and long lines throughout the morning (at registration, at food and drink purveyors, and even to walk in and out of designated areas: wristbands have to be scanned on entrance and exit of the second floor, where most of the action takes place. As a consequence, someone traveling from one panel to another—especially if the panels are on different floors—faces an intimidating gauntlet of pressed flesh. Hopefully the wristband scans are providing important demographic info, but surely there must be a better way; this situation is but one of several that need debriefing after this somewhat chaotic shakedown cruise.

It wasn't hard to squint and feel one was at the San Diego Comic-Con given the sampling of high-wattage movie-star talent and those big crowds. A difference from most cons: one can't squat in the main hall unless one has a VIP pass (not even a press pass will do). All panels are cleared, and people need to get back into a new line outside for the next event, if suffciently interested. This gives more people a chance to get into the room, which can't accomodate the entire paid audience, but it also contributes to a somewhat absurd shuffling of bodies and a general frustration among many con-goers. Most importantly, it's likely to drive revenue, as people learn the value (aha!) of the VIP pass.

I started Saturday by catching the tail end of the "Opening Ceremonies with Steve Wozniak." This appeared to be a genial extemporaneous ramble through whatever was in Woz's head as concerned the con and what it had to offer and why it was important. Standing a few yards from an identically dressed, uncanny Madam Tussaud's waxwork of himself, Woz evangelized about the VR area and discussed how he hoped to interest people in technology and technological advancement, noting that his own youthful superhero love had effectively come true through the (super)power(s) of technology. With the press of a button, Woz reasoned, he could now wield enormous power to achieve a goal, making him and all of us the equivalents of superheroes. Wozniak pointed out that art had to be experienced for itself and could not be satisfactorily explained in words (sorry, critics), so once having said his piece, bustled us off like a happy grandfather to see for ourselves.

Or, as the case may have been, to line back up for "Spotlight on Jeremy Renner." The film star came out and sat on the end table instead of the comfy chair provided him, at times getting up to stretch or pace casually. Though he frequently struggled to answer certain questions directly and demured from others, sometimes comically, he gave an overall impression of being at ease with the format, which he has been rolling with in Wizard Worlds for quite some time. Spending an hour answering the questions of mad-loving fans must be a pretty easy way to make a buck (not to mention those pricy autographs and photo ops: Renner charges more than Shatner), and indeed this crowd bathed Renner in unconditional love, not to mention lust (several con-goers confessed to be weak at the knees to have Renner looking at or talking to them—who knew?).

Prodded by questions from the audience, Renner talked about his breakthrough role of Jeffrey Dahmer, his impactful work on The Hurt Locker, and of course, all manner of questions about Hawkeye, his Marvel Comics character from The Avengers and the upcoming Captain America: Civil War. Renner smiled and laughed as fans insisted upon asking him about spoilers or which side he's on in that "civil war," which superhero he'd like to play if not Hawkeye and, endlessly, about possible Hawkeye spinoffs on the big or small screen. Especially given his high quotes, Renner proved "recklessly" generous in running off the stage to give a birthday girl a hug and posing for a couple of photos, one with a group of enterprising young journalists from Sacred Heart Nativity School (good on you, kids!).

Bounced from Room I, I tried running downstairs to Room 5 to catch some of the "Spotlight on Star Trek's Nichelle Nichols." Not yet having the lay of the land, which was crammed with bodies, this goal was a tall order. When I finally found the downstairs panel rooms, inconveniently located behind unclear signage and scads of registration lines, I realized the smallish room had long ago closed for entry as Nichols spoke to her wall-to-wall crowd. So back I went to Room I, where I could still gain entry to the "Spotlight on Nathan Fillion." Now, when I think of sci-fi raconteurs, Kevin Smith leaps immediately to mind, but I'm pretty sure Fillion has him beat. He sure has the love of his fans, and he's kind of like a younger version of Shatner, but better in all respects: more self-deprecating, much more amusing, and a whiz with a story.

Like Renner's panel, Fillion's didn't have much in the way of opening remarks: straight to the fan questions, which got Fillion talking about Firefly (including a nude scene for which Fillion claimed to have covered his privates with a Joss Whedon headshot, and why Fillion didn't hit on Gina Torres—two words: "Laurence Fishburne"), Drive (he couldn't remember the end game of the plot, but speculated), Halo (big fan, as well as a voice artist for animated films), Dr. Horrible's Singalong Blog (he knows, via Joss, only a song title and a new character name, but promises he, Joss, and Neil Patrick Harris are all on board for the much-discussed sequel), pranks on the set of Castle, and encounters with a moray eel and Christopher Walken. A highly entertaining hour was enjoyed by all.

The day's big event was, naturally, also guaranteed to cause scheduling nightmares: "Spotlight on Back to the Future" with Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, and Lea Thompson. The trio took the stage about a half hour late, due seemingly to crowd-control issues of herding first press and VIP and then general-admission ticket holders, all of whom also needed a ticketed QR code for entry to this special event. With ticketed photo ops to follow, the squeeze was on, but a moderated discussion and audience Q&A yielded a satisfying crash course in BTTF trilogy lore, and the actors' feelings about the still-strong phenomenon.

The day's big event was, naturally, also guaranteed to cause scheduling nightmares: "Spotlight on Back to the Future" with Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, and Lea Thompson. The trio took the stage about a half hour late, due seemingly to crowd-control issues of herding first press and VIP and then general-admission ticket holders, all of whom also needed a ticketed QR code for entry to this special event. With ticketed photo ops to follow, the squeeze was on, but a moderated discussion and audience Q&A yielded a satisfying crash course in BTTF trilogy lore, and the actors' feelings about the still-strong phenomenon.

The talent frequently credited Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis while bantering about stunt mishaps and favorite scenes, or graciously parrying random questions from pint-sized fans about whether or not they've seen Rick and Morty, or if the Doctor from Doctor Who might meet Marty and Doc. The kids had an excuse for odd questions; not so much the awkward and perhaps schizophrenic middle-aged man in a Robin the Boy Wonder costume, whose series of baffling queries all but shut down the panel. Only at a comic con, especially one that hasn't yet learned when to bring out the hook.

Fox got the most love from questioners. He recounted the tale of envying and ultimately winning the part in the Spielberg-produced movie, praised the brilliance of his co-stars' performances, and explained to another man with Parkinson's the thinking and process behind Fox's funhouse-mirror role in Curb Your Enthusiasm. Given that the talent has answered just about every question there is to ask about BTTF, I intended to ask each of the actors to describe what the other two are really like. Unfortunately, the panel ended just as I was about to ask my question, at the mic. My kingdom for a DeLorean!

SUNDAY, March 20, 2016:

I started my day at the rather sensationally titled "Geek Law 101: Intellectual Property Law Basics," where a panel of four lawyers (Angelo Alcid, Brian Focarino, Teri Karobonik, and Colin Sullvan) tag-teamed a lecture in copyright, trademarks, fair use, and the like. Despite a few interruptive questions meant to be held in reserve, they made it through a good, even entertaining, overview, but by the time they finished, only a few of many attendees were able to ask a question before Staff ejected everyone from the tightly scheduled space, to accommodate the crowd waiting for a Big Bang Theory writers' panel. Happily all four lawyers held court outside, offering their arcs and what information they could within the bounds of not offering specific legal advice.

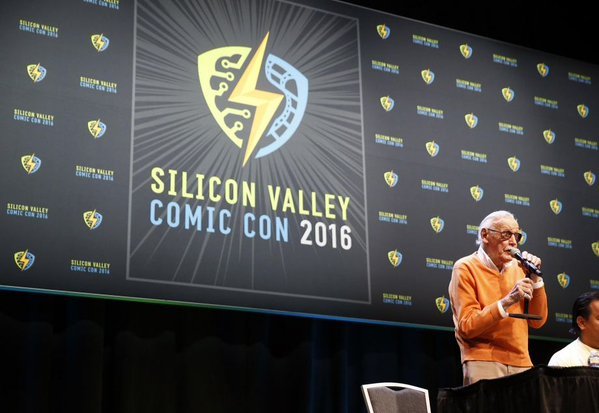

Next, it was time to line up upstairs at Room I, for "The Amazing Stan Lee." Addressing a roomful of long fans, 93-year-old Stan the Man sat with bodyguard/personal assistant Max (tasked with repeating any questions too indistinct for Lee's ears) and answered, with enthusiastic good humor, all comers. No controversies erupted about authorship, although Lee tipped his hat to creators Jack Kirby and Joe Simon during an answer about Captain America and ironically expressed envy of Rob Liefeld, the co-creator of Deadpool. The rest of the time, Lee accepted praise for creating Spider-Man, Thor, the Fantastic Four, et al. Lee answered lots of questions about the Marvel movies and his new career as what he calls a "cameo star"...the one and only.

Next, it was time to line up upstairs at Room I, for "The Amazing Stan Lee." Addressing a roomful of long fans, 93-year-old Stan the Man sat with bodyguard/personal assistant Max (tasked with repeating any questions too indistinct for Lee's ears) and answered, with enthusiastic good humor, all comers. No controversies erupted about authorship, although Lee tipped his hat to creators Jack Kirby and Joe Simon during an answer about Captain America and ironically expressed envy of Rob Liefeld, the co-creator of Deadpool. The rest of the time, Lee accepted praise for creating Spider-Man, Thor, the Fantastic Four, et al. Lee answered lots of questions about the Marvel movies and his new career as what he calls a "cameo star"...the one and only.

To the question of which writer, living or dead, with whom he'd like to collaborate, Lee cited Conan Doyle and Shakespeare, both for their vividly real characters, and the latter for his eloquence. Le showed his particular enthusiasm for a passage from Julius Caesar, reciting, "Romans, countrymen, and lovers! Hear me for my cause, and be silent, that you may hear: believe me for mine honour, and have respect to mine honour, that you may believe..." Lee also discussed Why "comic book" should be "comicbook" wanting to be Errol Flynn (if not a comics creator), settled a bet about whether an elevator with Thor's hammer in it would ascend (it would, but you wouldn't be able to pick it up off the floor of the elevator), and wrapped up the message with a last (but not the first) dig against DC. Lee maligned the unscientific introduction of flying into Superman comics and lauded the relative sensibility of Thor propelling himself by the weight of his hammer. And with an "Excelsior!" Lee was gone...

"Con Man: The Fan Revolt 14 Years in the Making" brought Alan Tudyk and Nathan Fillion together to celebrate the first season of their web series and hype the second. Joined by PJ Haarsma and Shannon Denton, the stars showed off images and key art from the upcoming comic book and video game spinoffs of Con Man before answering fan questions (and gifting signed mouse pads to the double-lucky who got their questions answered). Many of the questions, naturally, dealt with Firefly (dealing with cancellation and character deaths, for example, or why it was the best job ever), though others dealt with Con Man (like if Season Two would bring the actors together...answer: yes). Perhaps the most interesting answer brought both shows together, in recounting how Gail Berman sat down for a meeting on Con Man and had an awkward moment with Tudyk, since she was the person who cancelled Firefly ("No one says you put Firefly on the air," she lamented). The panel wrapped up with a Season One blooper reel.

"Closing Address: Steve Wozniak & Stan Lee" found the con's two famous front men joining forces to address another nearly full house in Room I. The event started late, with Rick White, Steve Wozniak's business partner welcoming the crowd and about to introduce Wozniak, who came out on stage before White had a chance. This set the tone for a disorganized, head-scratching panel that wasn't a closing address at all. Stan Lee came out for about ten minutes to kibitz with Woz and White, then White was handed a note from backstage. White proceeded to introduce Lee's daughter J.C. Lee, for whom her fathergave up his seat (he sat on the arm of the chair). After a minute or so of awkward compliments from J.C. Lee to Woz, White announced that Stan Lee—having set all this up to spend time with his daughter—would be leaving now with J.C. to hang out backstage. Ookay.

That accomplished, White tried an awkward bit of asking whether there were any actors in the audience who could step up and be Stan Lee. After too long a pause, Jon Heder emerged—not from the audience, but from backstage. White invited the audience lined up at the microphones to ask their questions for Stan Lee, and Heder gamely improvised answers. Woz took questions too, and it was all just a bit off and strange and, in hindsight, mostly a waste of time, given that this closing self-celebration drew a large crowd away from worthier panels. I fell for it too, but was expecting—well, I don't know what I was expecting, but something more...planned.

On that uncomfortable note, Silicon Valley Comic Con 1.0 came to a close. On balance, it was a plenty impressive event, albeit with many kinks to be worked out. At the "Closing Address," Woz repeatedly promised 2.0 would be even better, and I'm fairly certain that's true. One hopes that there were or will be some formal efforts to poll paid attendees about their experience, and not just Woz's anecdotal encounters with fans, which he described as being very happy (of course: they're talking to Steve Wozniak).

In fairness, the mob mood of the crowds always seemed festive during panels, which benefitted from an excellent A/V setup. Everyone seemed to be having a grand old time, and though one could hear grousing between events about various injustices of disorganization, the staffers I dealt with (even on Sunday, when I didn't wear my press badge) were always polite and good-natured. Frustrations are par for the comic-con course, so I'm sure the event will be remembered fondly and be even more successful in future. The real question is: after this year's excitement, will the Con and San Jose Convention Center be able to accommodate the future crowds?

Watch this space for more about Silicon Valley Comic Con 2016!