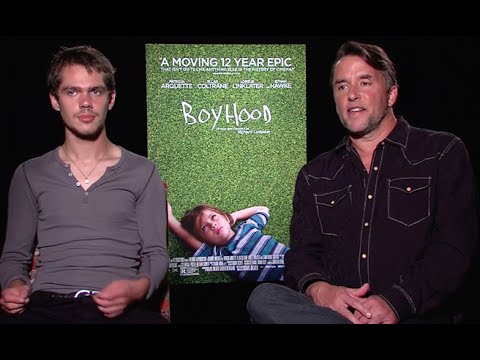

Quietly but surely, Richard Linklater has become one of American cinema's most important auteurs. Since his bracing indie debut Slacker, he has endeared himself to a cult audience (with films like Waking Life, Tape, and Fast Food Nation), but he has just as well proved his capability within the movie mainstream (School of Rock, Bad News Bears). Arguably most of his films fall somewhere in between those poles, in the nether region conventional wisdom says the movie industry has all but squeezed out (Dazed and Confused, The Newton Boys, Me and Orson Welles, A Scanner Darkly, Bernie). Perhaps best known to date for his trilogy Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight, Linklater has finally released his secret magnum opus, Boyhood, which he shot over a period of twelve years with the same cast. I met with Linklater—on his busy, busy press tour for Boyhood—at San Francisco's Fairmont Hotel.

Groucho: Oh, bless you for your stamina!

Richard Linklater: (Laughs.) Oh, well, it's—y'know! I used to work for a living; I was an offshore oil worker. (Laughs.) This is nothing. Just—so.

Groucho: Fair point. Alright, so though your new film is arguably more about time—

Richard Linklater: Mm-hm.

G: Or human existence itself, it is called Boyhood, so let's start there.

RL: Yeeah. You pick your perspective. Y'know, films have to have a point of view. And this is—it's his point of view, but it's still a portrait of a family. It's girlhood, it's motherhood, it's parenthood, it's familyhood, but if I had to narrow it down, it would be "boyhood," but it's everything else too.

G: What do you feel the finished film expresses about boyhood, and how might it have differed had you made "Girlhood," let's say?

RL: Mm-hm. Well, it's the perspective of a kid going through life. And it's kind of a view of his sibling, his older sibling, and his parents. Which is kind of a—that's a very limited view, as you're young. And that view widens as you get older. So it's almost like an unreliable narrator. Like people say, the stepfathers are awful. It's like, well, yeah, but that's his point of view of them. I'm sure they have their good qualities. But as a kid, you don't understand your parents. He doesn't know why his parents got divorced. And I wanted the film to share his point of view. Like the film doesn't come out and show them breaking up. There's nothing in the film that the audience knows that he doesn't. You know what I mean? So if there's a mystery—and it is always mysterious: why did your parents divorce? You never really get—they never tell you. They just give you the result: oh, Dad's moving out, or oh, we're moving. You don't know all the reasons. You're just being kind of thrust around at others' behest. That's what being a little kid feels like. But, y'know, you get older, and there's this thing, like your true self is emerging, and at some point, it's your own opinion, it's your own taste, your own skeptical thinking. And pretty soon he's got his own car, a job, a girlfriend: he's off on—the other people start to recede from the narrative a little bit. The first half of the movie, he's pretty much a—it's more reactive. That's how I felt, kind of. These little moments, but you don't control the world. So it's coming of agency, I guess.

RL: Mm-hm. Well, it's the perspective of a kid going through life. And it's kind of a view of his sibling, his older sibling, and his parents. Which is kind of a—that's a very limited view, as you're young. And that view widens as you get older. So it's almost like an unreliable narrator. Like people say, the stepfathers are awful. It's like, well, yeah, but that's his point of view of them. I'm sure they have their good qualities. But as a kid, you don't understand your parents. He doesn't know why his parents got divorced. And I wanted the film to share his point of view. Like the film doesn't come out and show them breaking up. There's nothing in the film that the audience knows that he doesn't. You know what I mean? So if there's a mystery—and it is always mysterious: why did your parents divorce? You never really get—they never tell you. They just give you the result: oh, Dad's moving out, or oh, we're moving. You don't know all the reasons. You're just being kind of thrust around at others' behest. That's what being a little kid feels like. But, y'know, you get older, and there's this thing, like your true self is emerging, and at some point, it's your own opinion, it's your own taste, your own skeptical thinking. And pretty soon he's got his own car, a job, a girlfriend: he's off on—the other people start to recede from the narrative a little bit. The first half of the movie, he's pretty much a—it's more reactive. That's how I felt, kind of. These little moments, but you don't control the world. So it's coming of agency, I guess.

G: So how different was the filmmaker who started this process from the filmmaker who ended this process?

RL: (Laughs.) Uhh...gosh! I wish I could say, "Very different," but not really. I mean, not—I wanted the film to feel like one film. It would be an insult to say, "Oh, the filmmaking got better, or evolved, or it's a different movie at the [end]"—no.

G: Well, you had a plan for that [consistency].

RL: Yeah. There was a plan to execute, and we executed it. That was as simple as that. But, I mean, twelve more years of life. Y'know? What's the difference between being 41 and 53, you know? It's like, well, that's some years of life, and hanging out with this material: growing up, parenting, and doing those things over the—certainly the parenting part, and contemplating growing up, so I think I have deeper feelings about all of the above, but I don't think I'm demonstrably different. Unfortunately! I don't know if you can be! You can have experienced a deeper—a depth of your feelings about it, but I don't know if externally you change much. I would like to think you could.

G: It's often said that actors who grow up on film, so to speak, have these expensive home movies. And that's true of Ethan Hawke, who started as a child actor—

RL: Yeah! You want to hang out with little Ethan, go watch Explorers.

G: Yeah, right.

RL: Yeah.

G: And of course for Ellar [Coltrane] with this process. Have you talked with actors about how they feel about that phenomenon? How does Ellar feel about it?

RL: Yeah, well, it's a delicate thing! And they never saw the footage as we were doing it. That just didn't seem natural. They never asked, but it was my instinct not to show 'em. I don't usually show footage to actors I'm working with. Unless there's some specific reason. But I knew it would be a very powerful thing when they did watch it. I was kinda—I felt a little better knowing they would be adults by the time they saw it. But even as we were shooting, I knew, "Ooh, this is going to be a powerful thing in your life. Even if no one ever sees it—who knows what the culture might make of it, and your relation to that—that's kind of out of our control." But just their own relation with it, I knew that would be pretty powerful. So I gave 'em a DVD. I gave Ellar a DVD and said, "Just, y'know, I would suggest—you gotta build your own relationship with this thing. It's not you. This is a fictional character you're playing. But it is a record of you, of what you look like." And every actor: you want to hang out with a young Jimmy Stewart, go watch that movie! Old Jimmy Stewart? Y'know, it's a powerful record that you existed. (Laughs.) As a person! And I don't think actors—they're not really motivated by that specifically, but it's kind of an offshoot of being in this industry. Ellar said he watched it several times. And went through the gamut of emotions. But it was all kind of good. It's his life, and he kind of came out of it feeling—and continues to—he can speak very eloquently about it. He's a very thoughtful, sensitive guy, so I'm so impressed by him. My daughter on the other hand (chuckles), she's kind of like, "Oh my God, look how fat I am! Y'know, she's much more body-critical. And I hate to break it down on gender lines, but she's just a little more sensitive about that, but I think she—it helped to watch it in a theater with a thousand people. When you think you're dorky and horrible, to hear everybody liking and appreciating your performance, you hope that overrides the self-critic a little bit. But, young women: it's tough, man! It's tough to be a human, but it's really tough to be a young woman.

RL: Yeah, well, it's a delicate thing! And they never saw the footage as we were doing it. That just didn't seem natural. They never asked, but it was my instinct not to show 'em. I don't usually show footage to actors I'm working with. Unless there's some specific reason. But I knew it would be a very powerful thing when they did watch it. I was kinda—I felt a little better knowing they would be adults by the time they saw it. But even as we were shooting, I knew, "Ooh, this is going to be a powerful thing in your life. Even if no one ever sees it—who knows what the culture might make of it, and your relation to that—that's kind of out of our control." But just their own relation with it, I knew that would be pretty powerful. So I gave 'em a DVD. I gave Ellar a DVD and said, "Just, y'know, I would suggest—you gotta build your own relationship with this thing. It's not you. This is a fictional character you're playing. But it is a record of you, of what you look like." And every actor: you want to hang out with a young Jimmy Stewart, go watch that movie! Old Jimmy Stewart? Y'know, it's a powerful record that you existed. (Laughs.) As a person! And I don't think actors—they're not really motivated by that specifically, but it's kind of an offshoot of being in this industry. Ellar said he watched it several times. And went through the gamut of emotions. But it was all kind of good. It's his life, and he kind of came out of it feeling—and continues to—he can speak very eloquently about it. He's a very thoughtful, sensitive guy, so I'm so impressed by him. My daughter on the other hand (chuckles), she's kind of like, "Oh my God, look how fat I am! Y'know, she's much more body-critical. And I hate to break it down on gender lines, but she's just a little more sensitive about that, but I think she—it helped to watch it in a theater with a thousand people. When you think you're dorky and horrible, to hear everybody liking and appreciating your performance, you hope that overrides the self-critic a little bit. But, young women: it's tough, man! It's tough to be a human, but it's really tough to be a young woman.

G: True. I want to go all the way back for a minute. What was the original structural blueprint? What made it all the way through from that original plan, and what changed?

RL: Oh, everything made it through! Nothing changed. It was all kind of—I mean, I'm not talking about a script; I'm talking about, oh, y'know, you're gonna go back to school, you're gonna move, you're gonna have a new husband and the family's going to move again, the divorce. All the big stuff—the outline of your life, as you might see it—it was going to end with you going off to college. That was all set, and that never changed much. But the little things, the year to year minutiae, it was really designed to incorporate that on a year-to-year basis.

G: Yeah, how did you go about that checking in, on an annual basis? I assume you needed to do that not only annually but with some lead time before that year's shooting to kind of contemplate—

RL: Yeah! It started with—at the end of the shoot, I would talk to the actors, like "Okay, next year, here's what's coming." And then I had the year to think about it, and so did they. And it's not uncommon I would get a call from Ethan: "Hey, Rick. I'm thinkin' about that scene. What if—" Y'know, like, boom! And we're off to the races. "Could we incorporate that? What are you thinking—?" And Ellar too: I would talk to him, and maybe give him an assignment. Y'know, let's say the second half of the movie. When he was a full-blown collaborator. It was just like "Hey, this is what's coming next year. In the next year, I want you to write down everything you talk about in the—" You know, like "You need to reveal more about yourself here. Let's really have this—" So it was great. It was a real wonderful collaboration. Patricia and I were in touch here—but we could get up to speed very quick, too. Maybe if she was real busy, and I was real busy, and it's maybe only three or four weeks from shooting, I could call her up and say, "Hey, in three weeks, we're shooting," and we'd have a long conversation. 'Cause it was something we were always thinking of, year round. She said even when she was working on other things, it was kind of—for all of us it never hit a back burner. I think it was always on a middle burner or a front burner.

RL: Yeah! It started with—at the end of the shoot, I would talk to the actors, like "Okay, next year, here's what's coming." And then I had the year to think about it, and so did they. And it's not uncommon I would get a call from Ethan: "Hey, Rick. I'm thinkin' about that scene. What if—" Y'know, like, boom! And we're off to the races. "Could we incorporate that? What are you thinking—?" And Ellar too: I would talk to him, and maybe give him an assignment. Y'know, let's say the second half of the movie. When he was a full-blown collaborator. It was just like "Hey, this is what's coming next year. In the next year, I want you to write down everything you talk about in the—" You know, like "You need to reveal more about yourself here. Let's really have this—" So it was great. It was a real wonderful collaboration. Patricia and I were in touch here—but we could get up to speed very quick, too. Maybe if she was real busy, and I was real busy, and it's maybe only three or four weeks from shooting, I could call her up and say, "Hey, in three weeks, we're shooting," and we'd have a long conversation. 'Cause it was something we were always thinking of, year round. She said even when she was working on other things, it was kind of—for all of us it never hit a back burner. I think it was always on a middle burner or a front burner.

G: In some ways, maybe because of the epic scope of it, too, this seems like a film that deals with a lot of what we see in your films over your career, like the conversation and perception and philosophy are all kind of in there. What did you hope to say about time and about life, and did the process teach you anything about time and about life?

RL: (Exhales.) I think it just heightened the sensitivity toward it. I mean, I've always kind of worked in narrative where time is probably a big element of the structuring of a movie. I think I've kind of gotten rid of plot, like some traditional notions of plot and replaced it a lot with structure—time, in particular—time structures. That feels more innate to how we process life, y'know, as it goes by. So I think the film—I really wanted something as simple as how it feels to grow up, or how it feels to live through these years. In a two-hour-and-forty-minute period, I wanted to feel like twelve years went by. Y'know? And that can be a real feeling. Just think back twelve years in your life, and zhoom! It can go pretty quick. So, more dramatic when you're a little kid: twelve years is such a large percentage of your life, double—y'know, from where Ellar's starting at the beginning, it's twice his life length. There's no adult equivalent of that. But yet time moves differently at different ages. That's what's very clear to me now. I mean, I knew it then intellectually, but I think having studied it under the—just the life experience of this. People say, "Oh, have you talked to Ellar lately?" And I'm like "Yeah! I just saw him—yeah, not so long—y'know, maybe six months ago. Yeah, I see him all the time." Ellar comes—"Have you seen Rick lately?" "No, I haven't heard from him in a long time." Same six months, y'know? It's kind of like "Oh, yeah! Six months is a long time to a kid!" It's different. Time is different. So it was a constant reminder, working with these kids under a microscope, kind of like this: how different time moves at different points in your life.

RL: (Exhales.) I think it just heightened the sensitivity toward it. I mean, I've always kind of worked in narrative where time is probably a big element of the structuring of a movie. I think I've kind of gotten rid of plot, like some traditional notions of plot and replaced it a lot with structure—time, in particular—time structures. That feels more innate to how we process life, y'know, as it goes by. So I think the film—I really wanted something as simple as how it feels to grow up, or how it feels to live through these years. In a two-hour-and-forty-minute period, I wanted to feel like twelve years went by. Y'know? And that can be a real feeling. Just think back twelve years in your life, and zhoom! It can go pretty quick. So, more dramatic when you're a little kid: twelve years is such a large percentage of your life, double—y'know, from where Ellar's starting at the beginning, it's twice his life length. There's no adult equivalent of that. But yet time moves differently at different ages. That's what's very clear to me now. I mean, I knew it then intellectually, but I think having studied it under the—just the life experience of this. People say, "Oh, have you talked to Ellar lately?" And I'm like "Yeah! I just saw him—yeah, not so long—y'know, maybe six months ago. Yeah, I see him all the time." Ellar comes—"Have you seen Rick lately?" "No, I haven't heard from him in a long time." Same six months, y'know? It's kind of like "Oh, yeah! Six months is a long time to a kid!" It's different. Time is different. So it was a constant reminder, working with these kids under a microscope, kind of like this: how different time moves at different points in your life.

G: Alright, well, it's been great talking to you. I wish we had more...time.

RL: Yeah! The irony of a time project, and you get a mere (leans over to check time index on recorder)—well, we're coming—(wistfully) not even a minute per year—

G: Right!

RL: Of what we shot, do we get to talk about it.

G: Yeah.

(Both laugh heartily.)

G: That's funny.

RL: Anyway!