Man on Wire

(2008)

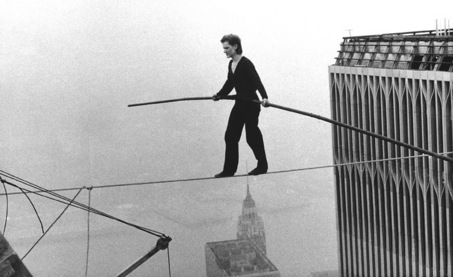

Anyone who has ever been talked into pitching in money, time, resources, or emotional energy to an artistic endeavor knows that there's a certain kind of zealous personality that makes art from scratch possible. Endemic to this character is passion, as well as vision. Though sometimes the artist effectively subsumes himself or herself into the art in a spirit of communal creation, this character is in most cases selfish, whimsical, and half-blind with tunnel vision, qualities arguably necessary to follow through to the completion of a work of art no one else could conceive or dare. James Marsh's engrossing new nonfiction film Man on Wire documents just such a character: Philippe Petit, who in 1974 broke into the World Trade Center and performed a 45-minute high-wire act, to and fro, across the 200-foot span between the Twin Towers.

Anyone who has ever been talked into pitching in money, time, resources, or emotional energy to an artistic endeavor knows that there's a certain kind of zealous personality that makes art from scratch possible. Endemic to this character is passion, as well as vision. Though sometimes the artist effectively subsumes himself or herself into the art in a spirit of communal creation, this character is in most cases selfish, whimsical, and half-blind with tunnel vision, qualities arguably necessary to follow through to the completion of a work of art no one else could conceive or dare. James Marsh's engrossing new nonfiction film Man on Wire documents just such a character: Philippe Petit, who in 1974 broke into the World Trade Center and performed a 45-minute high-wire act, to and fro, across the 200-foot span between the Twin Towers.

Marsh's show and tell stays resolutely focused on the WTC "coup" (as Petit and crew called it) and leaves Petit's character implicit in the telling. Even the collage of remembrances by Petit's intimates (lover Annie Allix, chief conspirator Jean-Louis Blondeau, and seemingly every significant member of Petit's Impossible Missions force) mostly reveals character through action and reaction: what Petit did for them and to them, and the feelings he brought to the fore. Nothing in the film speaks more loudly than the quiet sobbing of more than one of these talking heads as the past once more becomes present.

By their excitable nature, Petit's own monologues are equally revealing about the charisma necessary to lead a team of followers into what could easily be an assisted suicide (at best) and what promises to involve criminal arrest (clearly part of the frisson that attracted Petit: Allix recounts his devotion to heist movies). Petit recalls a research mission that confirmed his whim was somehow both folly and unswerving destiny: "Slowly I thought, 'Okay, now it's impossible. That's sure. So let's start working.'" That word "impossible" may be the most frequently uttered in a film that disproves the point. In one of the film's truest musical choices, Marsh inserts Walter Murphy's "A Fifth of Beethoven" to reflect a '70s brand of irreverent artistic hubris. (Michael Nyman contributes the nicely understated score.)

In addition to the well-assembled oral history, Marsh employs skillful, restrained black-and-white recreations to fill in the gaps in a wealth of remarkable archival footage and photos depicting Petit's brainstorming sessions, rehearsals, and "the coup." Marsh unnecessarily complicates the timeline of the events leading up to and including Aug. 7, 1974, jumping backwards and forwards once or twice too often, and his determination not to overstate anything results in the lack of firm modern context (no title cards at the end to fill in the 34-year interim). But these are minor quibbles in the rich and visually well-documented telling of a fascinating story.

The quixotic dream of a man Allix describes as "so excessive, so creative" found Petit going stratospheric just as Nixon was going down, and the great irony of the story is its triumph of the visionary individual over authoritarian bureaucracy. Once the initial moment of shock and awe passed, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey swallowed its chagrin and became Petit's latest convert. Suddenly, a structure critiqued as a monolithic eyesore had been transformed into a place of wonder. 27 years later, the buildings' sudden absence would make the heart grow yet fonder, another point Marsh's film makes not with any mention, but simply by telling Petit's story.