"In Ancient Sparta, important matters were decided by who shouted loudest."—Sister Aloysius Beauvier, Doubt

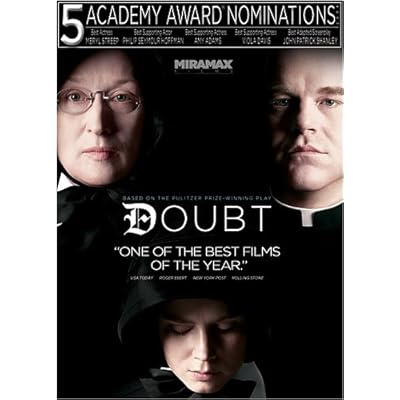

There's a modern theatrical tradition: let's call it the verbal cage match. It's made to showcase actors as they embody conflicting points of view. Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee's Inherit the Wind is a prime example, as is David Mamet's Oleanna. Like Oleanna, John Patrick Shanley's Pulitzer Prize-winning play Doubt pits two characters against one another in an ambiguous situation that builds to devastating consquences, and as in Oleanna, the teetering balance of the two protagonist/antagonists locked in battle must be maintained for the piece's full power to emerge. Mamet's play, though, invites the audience to interpret events depicted in full view of the audience, whereas Shanley's inciting event, if it even is one, happens behind closed doors and off screen. In bringing Doubt to the screen, writer-director Shanley has handed off his two prime parts to two of our finest movie stars—Meryl Streep and Philip Seymour Hoffman—and they've arrived ready to rumble, every verbal blow fraught with subtext.

The plot is the essence of simplicity delicately twisted into something maddeningly complicated. It's 1964 at St. Nicholas Catholic parish in the Bronx. Masses draw a large congregation, who look at Fr. Brendan Flynn (Hoffman) with unwavering respect and admiration. At the parish school, the Sisters of Charity have a stronger presence in the forms of principal Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Streep), 8th-grade teacher Sister James (Amy Adams) and others. Though the chain of command stretches above her to a number of men, the school is still Sister Aloysius' domain, and she will brook nothing she perceives as wrongdoing from the students or the adults. And Aloysius has grave doubts about Fr. Flynn, believing him to have, as Sister James delicately puts it, "taken an interest" in twelve-year-old Donald Muller (Joseph Foster), the school's "first Negro student." The priest has a bully pulpit on his side, but the nun has her convictions. The rub is that, in the absence of more than circumstantial evidence, we are never sure whether or not the priest is guilty.

In 2008, primed by the Catholic Church's sexual scandals, we all know what Aloysius suspects, without having to hear her speak the words. But her unshakable suspicions can be (and are) explained away by Fr. Flynn. Standing in the middle, Sister James wavers; described with disdain by Sister Aloysius as "a very innocent person," James holds the view that "the world is good, and we need only work together to overcome our problems," a simplistic and naive notion disproven by the complex conflict of her superiors (Alyosius shrewdly points out that James clings to her comforting simplicity). As Flynn intimates, people will see what they want to see, but Shanley carefully maintains the story's precious ambiguity: without it, the questions of faith, of doubt and certainty, lose their deeply troubling meaning. Like Oleanna, Doubt is a Rorshach test for an audience, and some see it as a lot of bluster with little meaning. Shanley's goal, though, is not to assert answers about moral and ethical behavior, but to ask questions. In this regard, Doubt is good to the last drop: the guilt-drenched final line is a prism revealing new facets of character and theme to ponder on the way out of the theater.

Doubt's allegorical central conflict accurately reflects the times through which we've just lived. There's a reflection of Blue State-Red State America in the story's clash of pre- and post-Vatican II attitudes (Flynn: "It's a new time sister." Aloysius: "There is nothing new under the sun"). Such issues, so vital in 1963, have mellowed but still fester. Flynn calls for "progressive education and a welcoming church," while Aloysius clings to the powerful mystery of the Church, one that she believes should strike awe and, yes, fear into the impressionable children of the school. (In this screen adaptation, those fragile children are never off screen for long, and Shanley and ace cinematographer Roger Deakins emphasize the dwarfing, size of the church and school buildings, the latter dominated by the eye of God watching from a high, stained-glass window. The eye watches Flynn, too, and Sister James remarks upon her vision of the finger-pointing hand of God. God's intimidating might is also in the ever-present hymns: "Lord above, we bow before thee...") When the judgmental Aloysius decries the threateningly secular Christmas song "Frosty the Snowman" as espousing "a pagan view of magic," it's impossible not to think of the many conservatives who today want Harry Potter banned from school libraries for the same reason.

Doubt's conflict also implicitly questions our nation's faith-based leadership since 2000, and the decade-defining decision to go to war in Iraq based on the assertion of weapons of mass destruction.

Father Flynn: You haven't the slightest proof of anything!

Sister Aloysius: But I have my certainty!

We're invited to consider who deserves to hold power, and how is it to be responsibly used. Even Aloysius confesses she's walking a dangerous path, though only out of necessity: "In the pursuit of wrongdoing, one steps away from God. Of course there is a price." It's also clear that Aloysius is driven by a certainty her sex is being treated unjustly, just as feminism was dawning in America. Shanley humorously depicts the old boys network of the church, with the patriarchal caretakers of dogma eating red meat, smoking, drinking, and laughing around the dinner table. Cut to the silent and austere dining room of the nuns: a reflection of Aloysius' serious devotion to her vows, but also a signifier that the women know their place, like it or not (Flynn, too, knows his, taking Aloysius chair when he meets with her in her office). Aloysius puts it bluntly: "Men run everything."

Above all, Doubt is existential. In an uncertain universe, how can we put one foot before the other without convincing ourselves that we are right? But on what do we base our decisions? Most people get the lay of the land, make a choice, and determine to go on believing in it, as all four principal characters do here. As the fourth character, Donald's mother, Viola Davis enters the movie, delivers what's effectively a gale-force aria, then exits again, leaving us shaken. On the basis of signs to which we're not privy, Mrs. Muller has concluded her son is homosexual and, as such, has her own fervent opinion about what should be done about the matter of Fr. Flynn and Donald. The scene raises more fresh questions in territory where most mainstream films fear to tread.

Sister Aloysius, the representative of so many fearsome Catholics of years past, is a character for the ages. While it's a shame Cherry Jones' commanding, Tony-winning performance couldn't be preserved here, Streep brings her own shadings. The fearsome woman Flynn calls "the dragon" here seems more of a prowling lioness, protecting her charges and keeping order and control, with sympathy only in the most discreet of circumstances and with ferocity when necessary. Perhaps she's the "fear itself" that's the only thing the children have to fear, or perhaps Flynn is, if he's "the devil" Aloysius labels him. Hoffman expertly makes Flynn specific without giving up his own opinion of the man's guilt or innocence. No matter what his actions were, Flynn believes he's innocent, having done what's best for Donald. Adams is (type)cast to perfection, and Davis gives a master class in winning (and deserving) an Best Supporting Actress nomination.

As director, Shanley does a fine job of making his parable more than literally larger than life on the screen; the story's tension has a visual representation in the equal presence of orderly symmetrical shots and extreme dutch angles . Shanley's evocation of a time and place of his childhood is skillful if not downright brilliant. The director also has a knack for symbolic and at times equivocal imagery: the little crosses on Aloysius' glasses that frame her face in devotion, the pressed flowers in Flynn's Bible, a lamp that seems to burn out on cue. Shanley's boldest symbolic stroke, a cold wind that blows through the film, certainly isn't subtle, but neither is the storm in King Lear, and Shanley earns his wind in Flynn's final sermon. It's a wind of change, and thus a wind of drama. Aloysius says, "The wind is so peripatetic this year. Is that the word I want?" It is. "Peripatetic" with a capital "P" refers to Aristotle, who taught philosophy on the move, while walking in the Lyceum.

As it was for the theater, Doubt is a new classic for the cinema. Streep's masterful relationship with the camera is an undeniable asset, and her place in the ensemble contributes most mightily to the film's Old Hollywood greatness: star power, all-around craftsmanship, and writing that's fertile with humor, drama, and ideas. In a season that's become relentlessly dour in pursuit of Oscar gold, here's a fall prestige picture that's brisk and never less than entertaining.

|

|

|

Miramax brings Doubt to Blu-ray in a clean and lovely hi-def transfer that accurately recreates the film's look. Detail and contrast are excellent, and colors are spot-on. Sound is likewise unimpeachable, in a full-bodied DTS-HD 5.1 mix. The disc also offers a number of interesting bonus features, including a feature commentary with writer/director John Patrick Shanley in which he discusses the inspirations for his play and the joys and challenges of adapting it into a film.

"From Stage to Screen" (19:09, HD) examines the play's adaptation, the characters, and the film's making. Particpants include Shanley, technical consultant Sister "James" Margaret McEntee, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Meryl Streep, Viola Davis, Amy Adams, production designer David Gropman, and there's a portion in which Shanley interviews Streep.

In "The Cast of Doubt" (13:52, HD), Entertainment Weekly's Dave Karger conducts a roundtable interview with Hoffman, Streep, Adams, and Davis.

"Scoring Doubt" (4:40, HD) focuses on composer Howard Shore's work; we witness a scoring session and get interviews with Shore and Shanley.

In "Sisters of Charity" (6:29, HD), Shanley and Streep preface interviews with real Sisters of Charity.

Doubt was, quite simply, one of the very best films of 2008; here's your chance to bring it home in a beautiful Blu-ray special edition.

|