Public Enemies

(2009)

True-crime story or romantic myth-making? This was the question I brought in to Michael Mann's Public Enemies, the question facing any John Dillinger movie and, though seemingly an either-or proposition, the question still on my mind when I walked out. Working from Bryan Burrough's non-fiction book Public Enemies: America's Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933–34, screenwriters Ronan Bennett and Mann & Ann Biderman hew reasonably closely to known incidents--enough for plenty of drama--but cannot resist framing Dillinger as a romantic figure.

True-crime story or romantic myth-making? This was the question I brought in to Michael Mann's Public Enemies, the question facing any John Dillinger movie and, though seemingly an either-or proposition, the question still on my mind when I walked out. Working from Bryan Burrough's non-fiction book Public Enemies: America's Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933–34, screenwriters Ronan Bennett and Mann & Ann Biderman hew reasonably closely to known incidents--enough for plenty of drama--but cannot resist framing Dillinger as a romantic figure.

Public Enemies ruthlessly limits its time frame to a period of just over a year, beginning with a fictionalized scene that conflates two separate 1933 prison breaks. Thrilling choreographed, the sequence establishes the film's aesthetic: sleek production design by Nathan Crowley (The Dark Knight); natty costumes by Colleen Atwood (Chicago); athletic digital-video photography by Dante Spinotti (Heat); outstanding location work; explosive violence from tough, brutal and well-armed men; and half-truth enacted by a movie star or two. (About that DV photography, though: the cameras Mann is using still aren't ready for prime time, a sadly distracting flaw in the film's visual scheme.)

Johnny Depp owns the film as outlaw Dillinger, the towering figure of "the golden age of bank robbery." There's no question that Depp gets the magnetism right, in a performance that intriguingly cuts more closely than ever to his own celebrity: if Captain Jack Sparrow is a rock star, John Dillinger is a movie star, a point underlined by his appearance in newsreels and his influence on pictures like Manhattan Melodrama (which Dillinger climactically attends at Chicago's Biograph Theater, in the film's most potent and emotionally penetrative scene).

Unfortunately, Depp's depiction of Dillinger utterly lacks the presumable crudeness of the man, the strong undercurrent of bitterness under his bravado (what lies beneath, instead, is fear of failure). Mann would rather show us that he's a man capable of crying over his girl. Though self-doubting, this Dillinger is too smooth ever to be truly brusque; despite his brutality, the filmmakers never rattle the audience into doubting whether or not he should be a folk hero. It seems clear that we're meant to love him, and mourn his passing from the national landscape. "I like baseball, movies, good clothes, fast cars, and you," he tells soon-to-be-girlfriend. "What else do you need to know?"

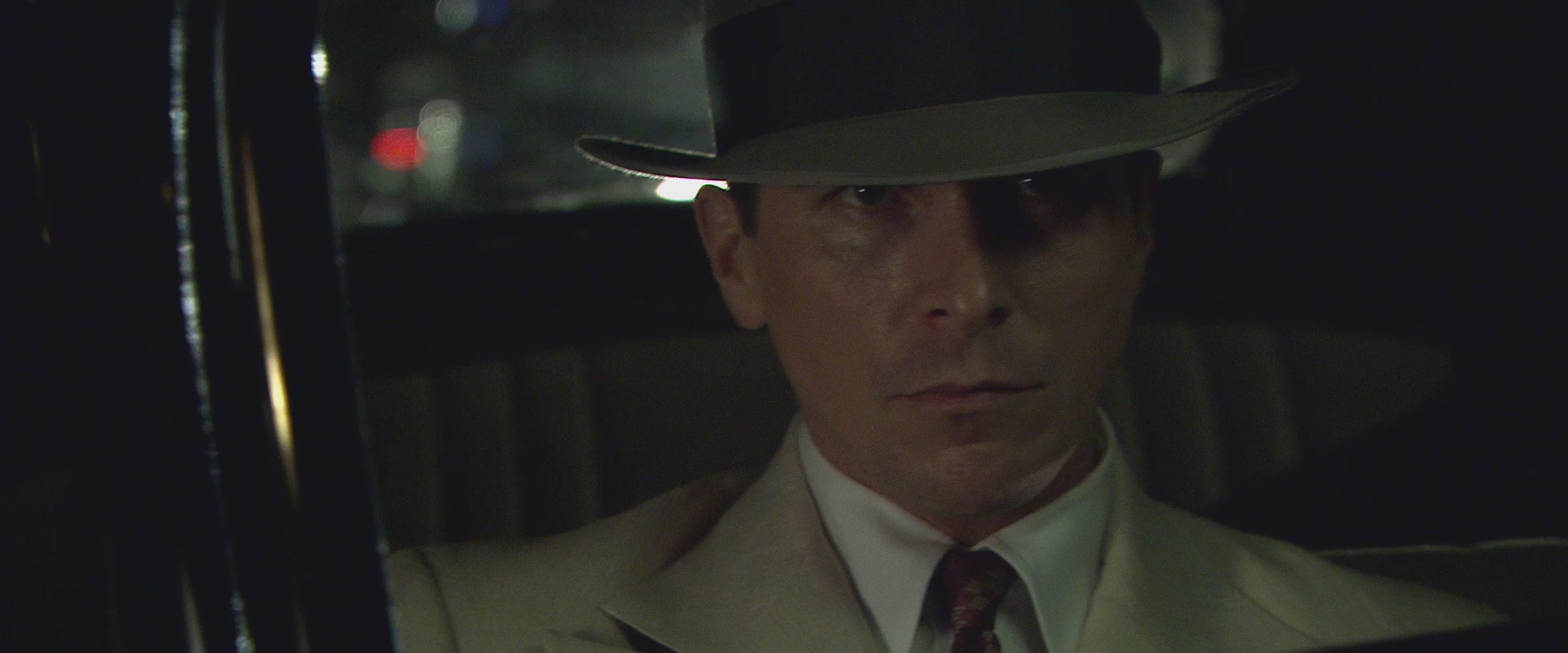

On the flip side is dour workaholic FBI Chicago Bureau Chief Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale). Public Enemies grants him even less backstory than Dillinger, and he's never seen off the clock: Purvis is simply the dogged Elliot Ness-type who will not rest until he's gotten his man. The script paints Purvis as the political pawn of smug FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup, failing to wrestle into submission an unfortunately phony dialect). Stymied by the experience and violent abandon of his foe, Purvis demands that Hoover reach out to the Chicago Police Department, telling him, "Our type cannot get the job done." That chink in the armor is as close as Purvis comes to humanity; with more experienced arms of the law appended to his team, Purvis immediately reverts to grim avenger closing ground on the likes of Baby Face Nelson (Stephen Graham) and Dillinger.

It must be said that Public Enemies is a successful Hollywood picture with a knack for entertainment through action and style, whether it's Diana Krall singing "Bye Bye Blackbird" or Depp leading a singalong of "The Last Roundup." And from time to time, Mann pauses to consider a matter of import: the backdrop of the Great Depression (when a housewife pleads to abscond with Dillinger), the economic impact of Dillinger's independent piracy within a criminal underworld working toward corporatization; the political ruthlessness that defined Hoover as a robber baron demonizing robbers, the shrewdness with which Dillinger regarded his public perception ("I don't like kidnapping...the public don't like kidnapping"). But the overall impression left by the film is a shallow one, as a jaunty but mostly empty story of a man who wants "Everything. Right now."

Given the cat-and-mouse game played by Dillinger and Purvis, comparisons to Mann's cops-and-robbers epic Heat are unavoidable. Beside stunning pyrotechnic displays of automatic weaponry, Public Enemies has a pow-wow between its stars at the halfway point: each character sizes up the other in the flesh and allows a smile to wryly tug into place. This time, the scene is not so much empathetic as disdainful, but there's an unspoken agreement between the adversaries that they are well-matched. Mann's now-signature use of ultra-tight close-ups further twins these alpha personalities.

Given the cat-and-mouse game played by Dillinger and Purvis, comparisons to Mann's cops-and-robbers epic Heat are unavoidable. Beside stunning pyrotechnic displays of automatic weaponry, Public Enemies has a pow-wow between its stars at the halfway point: each character sizes up the other in the flesh and allows a smile to wryly tug into place. This time, the scene is not so much empathetic as disdainful, but there's an unspoken agreement between the adversaries that they are well-matched. Mann's now-signature use of ultra-tight close-ups further twins these alpha personalities.

The big surprise is that Public Enemies turns out to be nearly as much about the relationship of Dillinger and his moll, erstwhile hatcheck girl Billie Frechette (Oscar's 2007 Best Actress Marion Cotillard). While the choice gives the film a strong female presence--including in timely scenes that deal with torture as an investigative technique--it also questionably romanticizes Dillinger's story. The final moments of the film--well-played by Cotillard and Stephen Lang (as Charles Winstead)--are nevertheless pure Hollywood hooey.

Speaking of hooey, we return to the question of true-crime or myth-making. Public Enemies comes tantalizingly close to the former; had Mann not proven sporadically scrupulous, his latest would have been a classic of the genre (among other white lies, the script also mangles the timeline of Baby Face Nelson for dramatic expediency). By leaning towards legend, Public Enemies sacrifices its true-crime credentials and loses its excuse for dramatic anemia, notwithstanding Dillinger's comment "The only thing that's important is where somebody's going." In the end, Mann gives us a cracking good action picture grafted with synthetic tragedy.